Welcome to The India Fix by Shoaib Daniyal: a newsletter on Indian politics. This week we're jumping off from Rahul Gandhi's explosive press conference identifying serious errors in the voter rolls. What does being a democracy mean if the voter lists, of all things, are not accurate?

Before we get to the newsletter, a quick announcement. I am doing a live audience recording of my podcast with Varun Grover – where we will also be discussing the state of our democracy. Varun will explain what it means to do political comedy in Modi's India.

Sign up here (it's on Monday).

As always, if you’ve been sent this newsletter and like it, to get it in your inbox every week, sign up here (click on “follow”).

Rahul Gandhi’s press conference on Thursday started off poorly: his slides suddenly disappeared from the screen even as he stood there, his face taut with anger. But once these technical glitches were sorted, what Gandhi disclosed was shocking. The leader of the Opposition alleged his party had found more than a lakh bogus voters in the Mahadevapura Assembly constituency in Bengaluru.

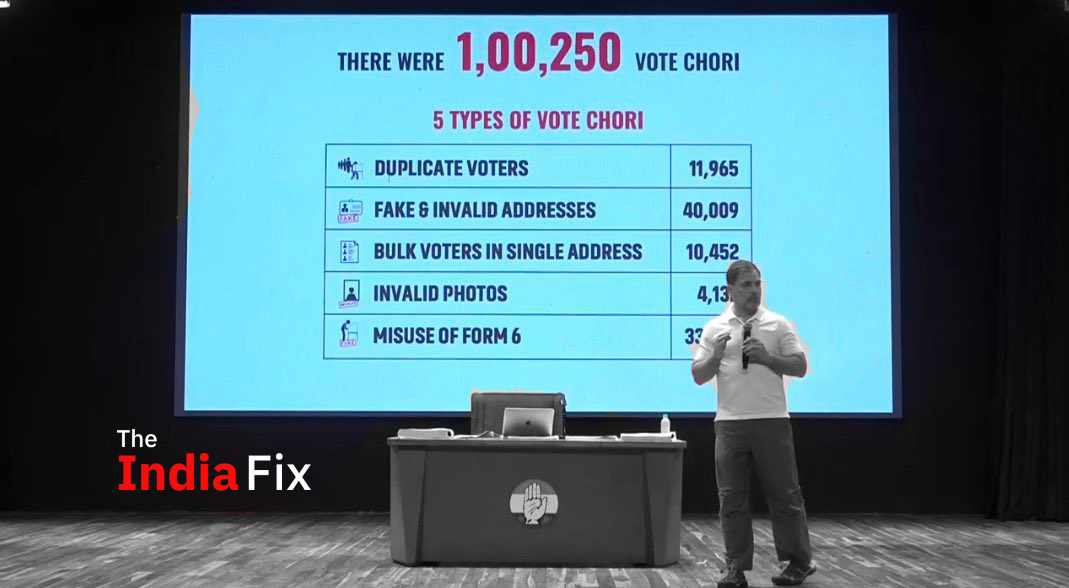

The press conference detailed five types of bogus entries in the electoral roll: duplicate voters, voters with fake addresses, bulk voters with the same address, invalid photographs (which made identification impossible) and enrolling fake first-time voters (using form six).

The examples Gandhi brought up were striking. Gurkirat Singh Dang, for example, appears four times in the roll with the exact same address. Another gent, Aditya Srivastava, votes across the country: Mumbai, Lucknow and in two booths in Bengaluru. One address in Bengaluru, a single-room house, has 80 voters registered to it. Other voters have strings of gibberish for address and father’s name (one was a Mr dfojgaidf). A 70-year-old lady called Shakun Rani enrolled as a new voter, resulting in her being able to vote twice.

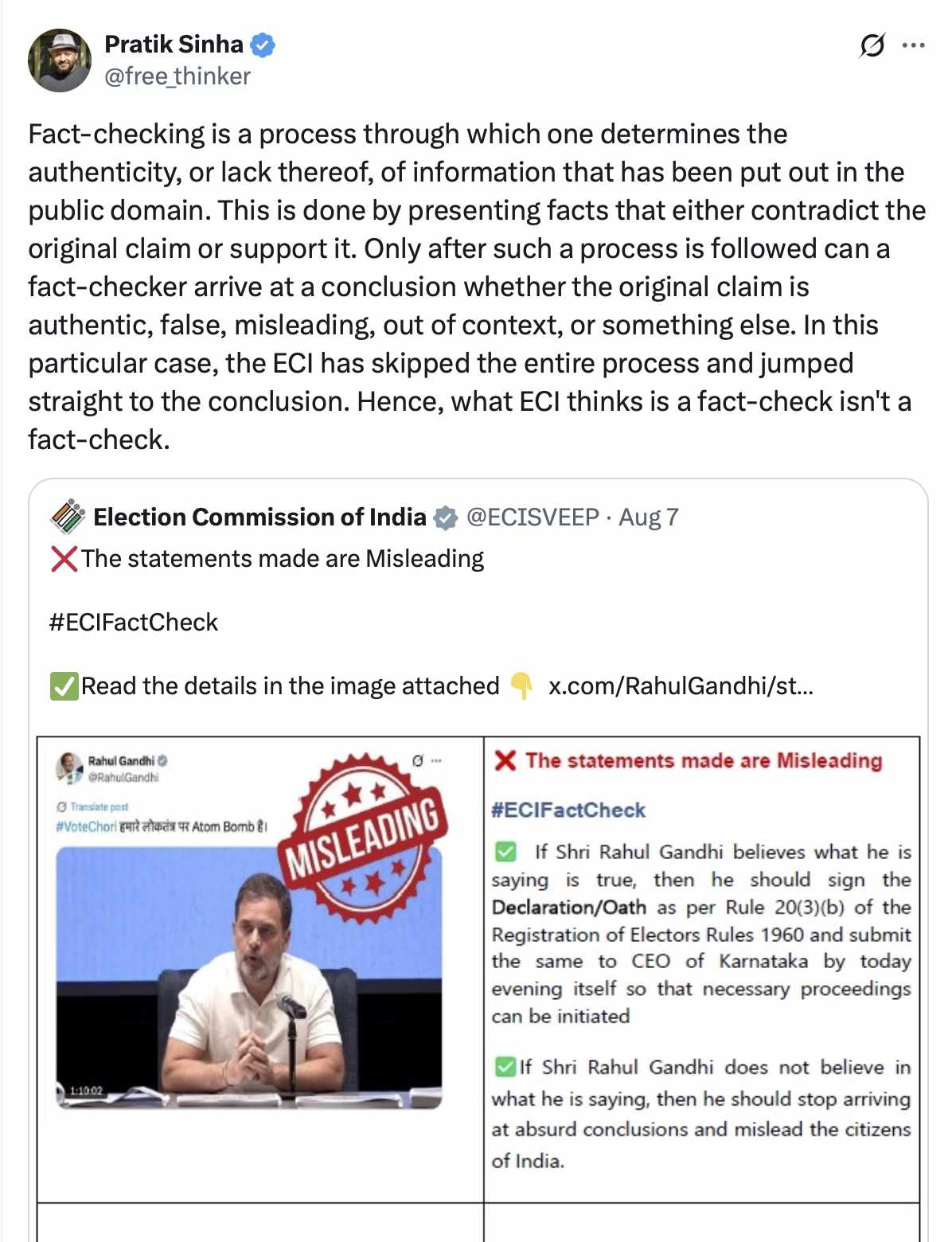

As striking as these examples were, even worse was the Election Commission’s response – or lack of it. It put out a tweet a few hours after Gandhi’s press conference with the tag #ECIFactCheck. Except there was no fact check: it did not actually rebut Gandhi. In fact, it said it would only take action if Gandhi swore an oath. It is unclear why the Election Commission does not think that errors in the voter roll deserve urgent action. Or why it has not agreed to demands by the Opposition to provide machine-readable voter rolls, which would make identifying errors a cinch.

Rising doubts

The Election Commission’s non-response was doubly troubling given this is not the first time doubts have been expressed over the health of India’s voter rolls.

Reporting by Scroll has found multiple complaints against voter roll exclusions. In 2023, the India Fix broke down a detailed research paper flagged multiple statistical anomalies with the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, part of which could be traced back to allegations that rolls were rigged.

In March, the Trinamool Congress flagged that Election Photo Identity Card numbers used in voter cards were not unique. Different voters across the country somehow had the same number. Again, the Election Commission was unable to explain the error even as it said that it would fix it going forward.

Even as the Election Commission is unable to explain how these errors are appearing, it is not holding back from even more drastic changes in voter lists. At present it is conducting a so-called Special Intensive Revision in Bihar with indications that women and Muslims are being especially targeted for exclusion. The design of the SIR, a de facto citizenship test with massive powers in the hands of the lower bureaucracy, makes it highly amenable to political pressure.

Betraying a legacy

Widespread doubts over voter rolls at the present moment stand in stark contrast to how universal adult franchise was introduced in India: the creation of a voter roll including all Indian voters was one of the first administrative tasks taken by independent India.

India had had elections under the Raj. But they were limited to elites. In 1937, the Raj’s biggest election ever, with Indians electing state governments, saw around a sixth of Indian adults qualify to be voters.

Within a few months of independence, the Constituent Assembly Secretariat, headed by bureaucrat BN Rau, was drawing up new rolls based on universal adult franchise. The political will for this was solid: the Congress had been asking for the vote for all adult Indians since 1928.

The result was, as Ornit Shani points out in her remarkable research on independent India’s first electoral roll, Indians became voters first and then citizens. Rolls were drawn up before the Indian constitution was drafted and adopted. “An electoral roll on the basis of universal franchise prepared and maintained as accurately and up-to-date as possible, was the plinth upon which the institutions of electoral democracy would rest,” Shani writes.

Unsurprisingly, this was a major factor for the Constituent Assembly as well. While moving an article which would lead to the formation of the Election Commission, BR Ambedkar, chairman of the drafting committee, was clear that no Indian should be excluded from the rolls “on the whim of an officer”.

Elections are the guts of a democracy. And voter rolls, in turn, are the guts of an election. Seven decades later, the widespread impression that the whims of officers – and politicians – are now deciding voter rolls is severely damaging to the idea of Indian democracy.

Write a comment ...